Gavin Wood’s video on Polkadot’s governance model is a masterclass in understanding blockchain governance from first principles.

I’ve summarized some of my key takeaways below, along with my own commentary, but I’d still recommend watching the entire thing. It covers some of the following topics:

- Why governance exists

- Why we need governance in cryptoeconomic systems

- Why cryptoeconomic governance models will power future internet economies (or even states).

- Why the behemoths – Bitcoin and Ethereum – are slow to evolve (hint hint, it has something to do with their governance models).

P.S: While Polkadot is in the process of moving to a new governance model, the same principles mentioned in this article still apply.

What is Governance?

Governance, in its purest form, is a set of rules and structures that guide decision-making in a system, to ensure the accountability of participants in that system (such as a state, network, or market). This accountability is the basis for participation in that system, as well as outward relations with other systems, as willing participants trust that economic and non-economic interactions will occur within the bounds of these rules.

These networks transcend nation states, corporations, and geopolitical alliances. For example, from a technological perspective, computer networks use standards and protocols such as TCP/IP & HTTPS as rule systems that determine how they communicate with each other and how data is processed through them.

Rules over a System, rather than within the System

In the video, Gavin emphasises governance as rules over a system (e.g. a constitutions, democracies, monarchies, parliaments), rather than rules within a system. While I first questioned this view, it actually makes sense, given that rules within a system operate within the confines of the ones presiding over the system. For example, in most countries, the process for bills becoming laws is governed by their constitution. This means that governance structures can override rules within the state, and have the power to change both themselves and these rules within (examples?). Also, while rules within a system (e.g. laws) are frequently updated by courts, changing governance structures are a highly contentious affair, usually preceded by, or resulting in secession, revolutions, and sometimes tragically, wars.

In the context of blockchain technology, you can think of rules within the system as the smart contracts you write for your dapp, as they set bounds on how users interact with your application. However, in order to build and execute those smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain, you have to work within the constraints of the protocol’s rules for state management, security, consensus, immutability, etc. Ethereum’s governance structure (rules over the system) determines these protocol rules, when to change them, and how these changes will occur (e.g. the decision to switch from Proof of Work to Proof of Stake). Porting your dapp onto a different network requires following a different set of rules (even though lately, most blockchains offer relative interoperability between different networks through bridges, even while enforcing their own protocol rules). Bitcoin’s hard forks, the ETH2 upgrade (other examples) are practical examples of governance in action, whether for good or bad.

The Problem with Existing Blockchain Governance

Blockchains are an effective mechanism for setting, maintaining and automating rules and accountability. On the blockchain, rules are implemented through machine-executable algorithms which create absolute (aka immutable) outcomes, while accountability (aka trust) is maintained through cryptographically secured statements & transactions that are distributed across all computers in the network.

However, most blockchain networks apply these rules only for applications within their ecosystem through smart contracts, and not on the protocol itself. Currently, most blockchain systems have off-chain governance mechanisms, where proposals, debates and referenda happen off-chain. As a result, quite ironically, blockchains have inherited characteristics of traditional governance structures which they aim to replace – upgrade processes are slow, contentious, and opaque. For example, ETH2 took over X years to implement, and Bitcoin has mostly remained the same since inception. In a fast moving world where things change rapidly, particularly in digital ecosystems, this is not the way to go.

What if we took the best characteristics of the blockchain – being an autonomous system for rules, consensus and accountability – and applied it over the network itself? What if proposals, referenda and upgrades to protocols happened on-chain?

Considering that blockchain technology enables autonomous digital economic systems, they need to implement governance structures as well.

If the blockchain and crypto will power Internet states (through network states), corporations (through DAOs), and markets (through DEXs), these networks will evolve much more rapidly than traditional states, corporations and markets. Hence it is critical that blockchain governance systems evolve into systems that enable quick and secure consensus, as well as easy and autonomous upgrades. Basically, using

There are several reasons why this vision for the future isn’t far-fetched:

- As Gavin points out, existing blockchain ecosystems already control billions of $ in economic value, even more than some developing countries.

- The distributed nature of blockchains means there is less friction to onboarding new “state members” or “citizens” onto the network.

- Most people are

Characteristics of Blockchain Governance

According to the Australian National Audit Office, effective governance has three characteristics:

- performance orientation

- effective collaboration,

- openness, transparency and integrity.

Adopting the same model, we can identify a good blockchain governance system by the following attributes:

- Performance Orientation: It enables autonomous, seamless updates of itself.

- Effective Collaboration: It encourages maximum participation of stakeholders (e.g. token holders) in decision-making.

- Openness, transparency, and integrity: Proposals, debates and referenda are permanently visible on-chain, and there are built-in mechanisms for managing consensus and dissent.

The Polkadot Approach

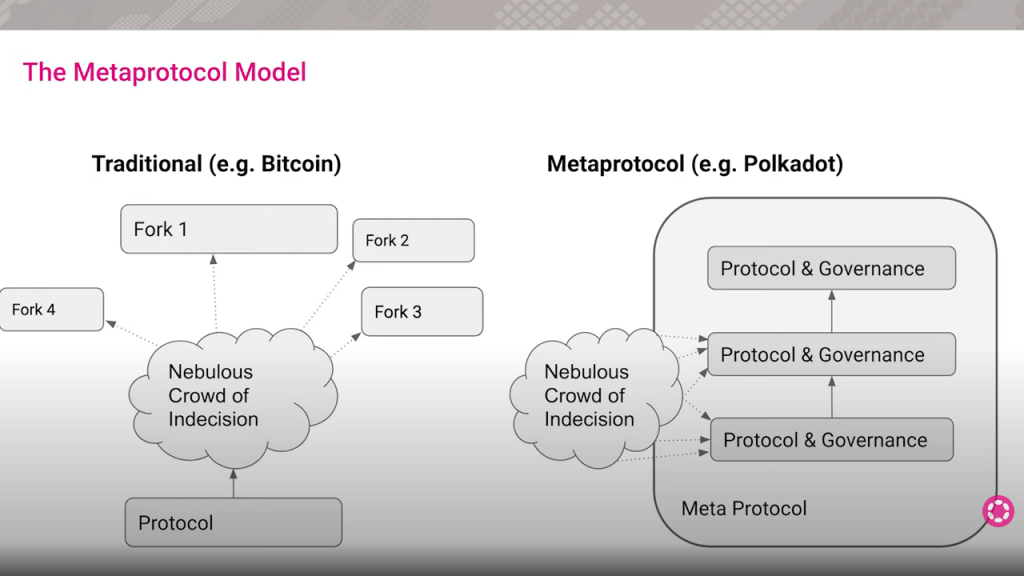

Polkadot is a meta-protocol. What does this mean? It means that, similar to how the Internet is a meta-network connecting millions (?) of other networks, Polkadot can host and connect hundreds of entire blockchain ecosystems, each defining their own rules and governance structures.

As a meta-protocol, Polkadot at its base layer does not define any rules for how a blockchain built on it should run. At the risk of over-simplification, think of it like empty acres of land on which you can build any type of structure, each serving its own purpose. Inhabitants of these structures can talk to each other and move between houses easily, while conforming to the rules of the house they currently inhabit. These structures are known as parachains. Parachains can build and implement their entire protocol and governance rules independent of Polkadot’s protocol and governance rules. In fact, the Polkadot blockchain itself is built using components of this base layer.

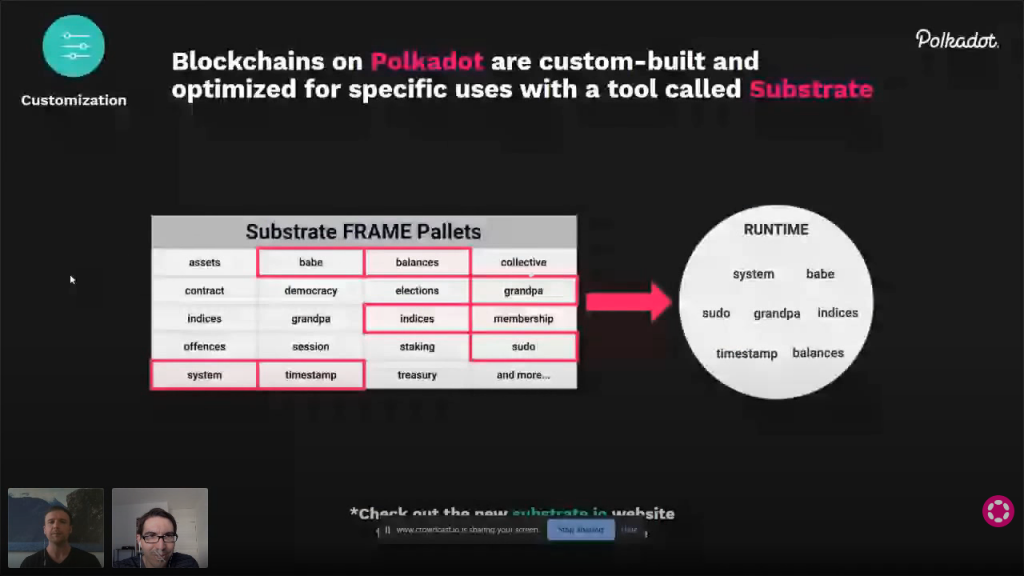

Substrate, a modular, flexible and extensible framework for building custom blockchains, enables this flexibility. Through its pallets, Substrate contains the building blocks of any blockchain network – consensus mechanism, smart contracts, among others, as shown in the image below. With Substrate, blockchain designers can pick and choose which components to use and customize, and then use protocols such as XCMP to pass messages to and from other chains on the Polkadot network.

Much has been written and said about the intricacies of Polkadot’s governance process, so I don’t see the need to rehash that. Even though they are based on the existing governance model, I personally recommend these resources to learn more:

- How Polkadot’s Governance Works by Gilbert Bassey

- Polkadot Wiki

Polkadot’s move to Governance v2 requires its own article, which I’ll write in the near future.

However, I’d still like to explain the basis for Polkadot, and why its approach towards governance closely mirrors the characteristics defined above.